Like many natural phenomena, precipitation can be both a blessing and a scourge to human life. On the one hand, it supplies our rivers and fields with water; on the other hand, it can cause floods, landslides, and other natural disasters. Either way, understanding and predicting the different types of precipitation is essential.

Gathering and analyzing precipitation data is key, but there are some places on Earth where this is tricky. One such place is the Tibetan Plateau, whose unique and challenging physical environment makes observing precipitation, either on the ground or from above via satellites, a problematic issue.

In terms of satellite-borne precipitation radar, the high altitude of the Tibetan Plateau leads to cases of mistaken identity when it comes to the specific types of precipitation. Most notably, because the height of the terrain on the plateau is close to the height of the freezing level in the atmosphere over non-plateau areas, weak convective precipitation can be misclassified as stratiform precipitation.

Recognizing this, in a recent study published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, Prof. FU Yunfei from the University of Science and Technology of China(USTC), along with colleagues from the China Meteorological Administration, first analyzed in detail the problems with the existing precipitation-type identification algorithm for satellite-borne precipitation radar, wherein they uncovered the reasons why the algorithm can fail in its identification of precipitation types over the Tibetan Plateau in summer, and then developed and tested a new one.

“It often seems that there is a desire to standardize everything in the natural world, whilst ignoring the obvious intricacies and diversities that exist at various scales,” explains Fu. “In our scientific field, meteorology, this also holds true; and in terms of the specific problem that we set out to solve in this study, the thresholds employed to identify types of precipitation are a specific example.”

Traditionally, based on observations in non-plateau regions, the approach to classifying precipitation is a simplistic one, ending with a somewhat binary result whereby precipitation is identified either as convective or stratiform.

With the new algorithm developed by Fu’s team, parameters such as maximum reflectivity factor, background maximum reflectivity factor, and echo top height are considered in greater depth to yield a more granular classification (types include “strong convective”, “weak convective”, “weak”, and “other”) that provides more useful information with far fewer identification errors.

Ultimately, the work of Fu and his team can be carried forward and adopted by the weather forecasting and modeling community to better predict the occurrence of different types of precipitation events in parts of the world where existing, standardized methods are less applicable. More specifically, as highlighted by the context in this particular paper, there are major benefits to be felt by communities living in mountainous regions like the Tibetan Plateau.

“It should be said, however,” ends Fu, “that there is still much to be done. In particular, we need to confirm the existence of stratiform precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau in summer. For a variety of reasons, this is still difficult to detect using satellite-borne precipitation radar measurements. This will be the next step in our research.”

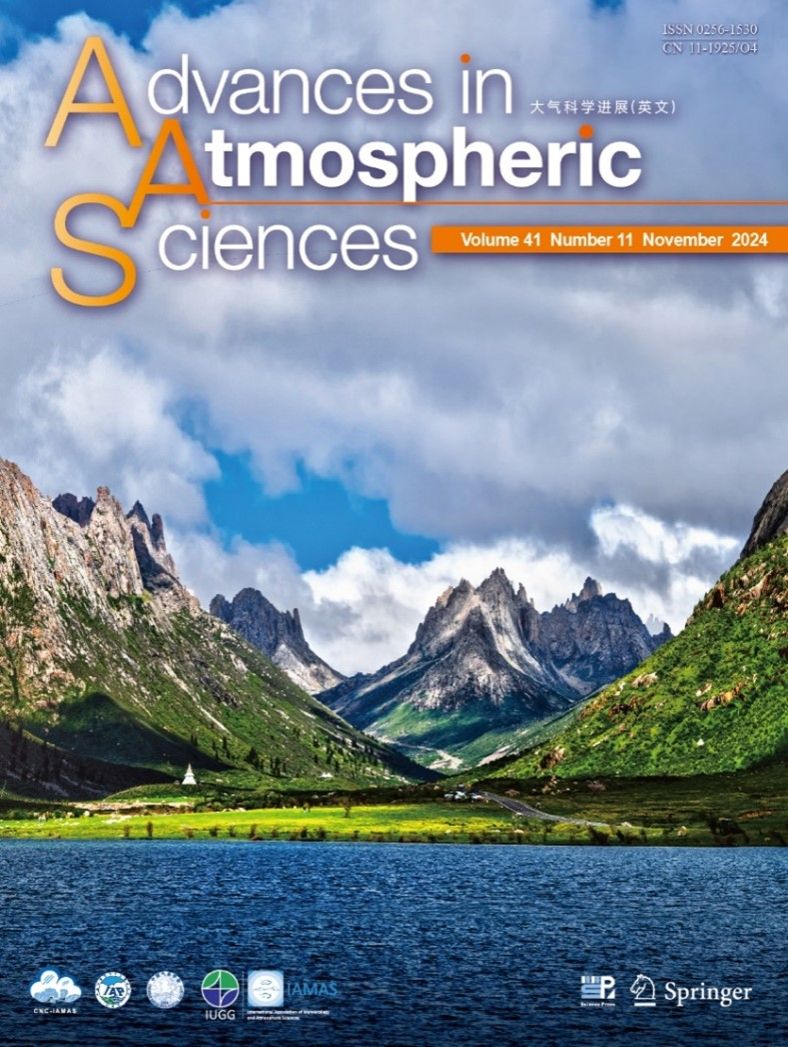

The cover of the Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. (Image by FU)

The paper is featured on the cover of issue 11 of Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. The cover photo was taken by FU in the Lianbao-Yeze Nature Reserve located at the junction of Xichuan, Gansu and Qinghai provinces, with an average elevation of more than 4000 meters above sea level. It shows convective clouds over the lake in the foreground, as well as over the far end of the mountain in the center.

Paper link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3384-7

(Written by LIN Zheng, edited by HUANG Rui, USTC News Center)