A prototype robot that might one day separate oxygen from ice on Mars has been created by chemists at USTC. It could help early explorers create breathable air.

If humans are to ever settle on Mars, they’re going to need techniques that rely on chemistry to produce the materials they will need to survive. Shipping necessities — such as food, breathable air and fuel — for ongoing usage to Mars would be prohibitively expensive.

Now, a team of researchers from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Hefei has taken a step towards meeting the needs of early Mars explorers. They have developed an artificial intelligence (AI) powered robotic chemistry lab that could potentially extract oxygen from frozen water on Mars.

This refrigerator-sized robot — capable of moving between lab workbenches and conducting experiments with its robotic arm — can design catalysts to split oxygen from water. Credit: University of Science and Technology of China

The Martian atmosphere contains little oxygen, a crucial resource vital for future human missions to Mars, for life support and also fuel. Researchers have been exploring ways to generate oxygen locally and one potential source could be water ice found in the polar regions. One promising method uses solar energy to decompose water into oxygen and hydrogen.

What’s missing?

However, this reaction isn’t easy to accomplish. It requires an oxygen evolution reaction (OER) catalyst — which typically contains metal oxides, such as iridium oxide or ruthenium oxide — to speed up the reaction. To avoid having to transport the catalyst to Mars, the system developed by USTC can automatically analyse the ores on the Red Planet and then use these to synthesize efficient OER catalysts.

“The entire process, including finding the optimal recipe for the catalyst, was completed without human guidance,” says Jun Jiang, a physical chemist who led the team at USTC. The work was published in Nature Synthesis1.

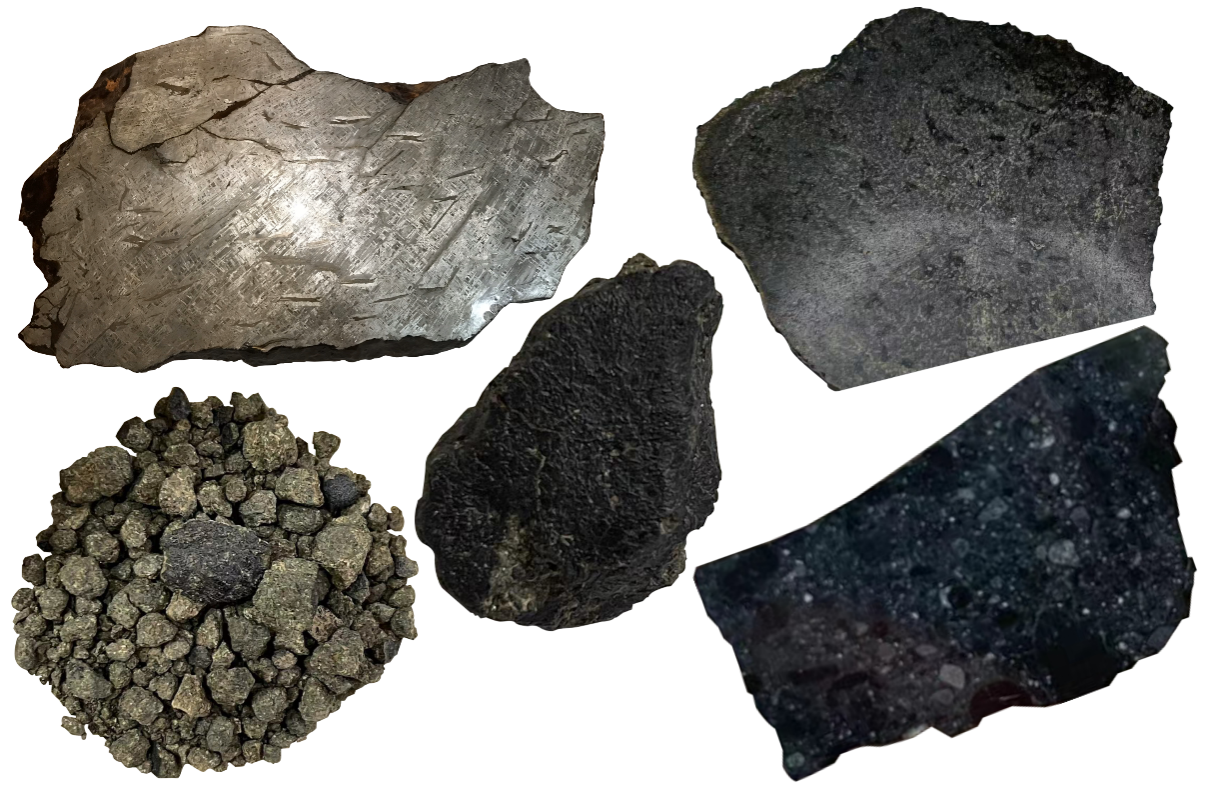

To simulate producing a catalyst from raw materials on Earth, the researchers provided the robot with Martian meteorite samples that approximate raw materials available on the planet’s surface.

The machine fires a laser at the sample and analyses the resulting light to understand the mineral composition, identifying elements and molecules it can use to build a catalyst. It then uses acids and alkalis to dissolve and separate substances, followed by an analysis of the resulting compounds.

This is where AI comes in – by comparing the products with a huge database formed by millions of chemical formulas.

It starts to screen for the optimal formula, and then synthesizes a catalyst capable of breaking down water. This is much faster than blindly making, and testing all possible material combinations.

Samples of Martian meteorites used in the experiment. Finding out their mineral composition is the first step for a robot chemist. Credit: University of Science and Technology of China

“Given five different local Martian ores as feedstocks, there will be three million possible formulas of catalyst. For a human to go through those formulas would take 2,000 years,” Jiang says. But the robot can reduce the whole process to about six weeks of work, and it succeeded in preparing a catalyst capable of producing 60 grams of oxygen per hour, more than enough for one human to breathe.

Earth to Mars

Here on Earth, Jiang’s lab is already using the robot chemistry lab to develop catalysts to improve the performance of fuel cells for hydrogen-powered electric vehicles.

The approach has come up with one that lasts for 14,000 hours, instead of those that last 4,000 hours which are currently available, says Jiang. The approach could also help chemists develop high-entropy alloys, a new class of materials that combine multiple elements in previously unknown formulations to give alloys with unique properties.

Jiang is currently talking to the China National Space Administration about the possibility of sending the prototype to the Moon, where it could test out its skills on lunar soil before tackling Mars.

References

1.Zhu, Q., Huang, Y., Zhou, D. et al. Nat. Synth (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-023-00424-1